NATIONAL DESK

Prosecutors Hope New Study of Handwriting Analysis Will Silence Skeptics

By ADAM LIPTAK (NYT) 1113 words

Handwriting analysis was the first investigative discipline developed specifically to help courts resolve disputes, and for most of the last century judges accepted it uncritically in cases involving contested documents like wills, ransom notes and forge

d checks. In the last decade, though, prompted by a United States Supreme Court decision on ''junk science,'' federal courts have grown increasingly skeptical.

Handwriting analysis was the first investigative discipline developed specifically to help courts resolve disputes, and for most of the last century judges accepted it uncritically in cases involving contested documents like wills, ransom notes and forge

d checks. In the last decade, though, prompted by a United States Supreme Court decision on ''junk science,'' federal courts have grown increasingly skeptical.

Now prosecutors are turning to a new computer-based study, financed by the Justice Departme nt, to restore the credibility of handwriting analysis as an investigative tool.

Last month, a federal court in Illinois rejected expert testimony on handwriting analysis, saying the research supporting it was too thin. Two weeks later, however, a Pennsylvania court came to the opposite conclusion, relying on the new study.

' 'The courts are genuinely divided, which is a peculiar place to be on a kind of evidence that purports to be scientific,'' said Jennifer L. Mnookin, a law professor at the University of Virginia.

Under the 1993 Supreme Court decision, known as Daubert , judges are now routinely called on to decide large questions about the scientific validity of entire disciplines like handwriting analysis. Judges, who generally have no scientific training, are also studying and occasionally rejecting evidence based on fingerprints, hair samples and ballistics.

Critics of handwriting analysis compare it to phrenology and astrology, and they say practitioners have resisted empirical testing for fear of being unmasked.

''I don't think anyone seriously calls it a science anymore,'' said Mark P. Denbeaux, a professor at Seton Hall Law School.

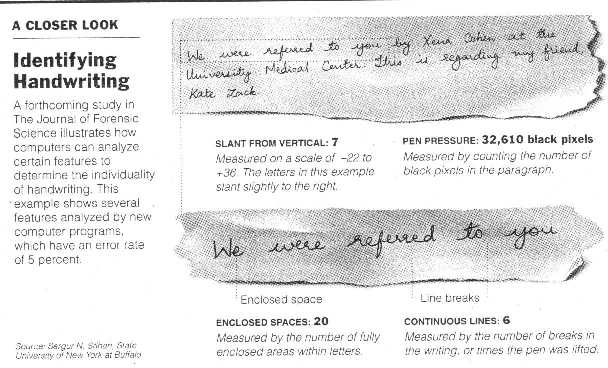

But proponents of handwriting analysis say that will change with the publication of the new study, which will appear in The Journal of Forensic Sciences in July.

Its p rincipal author, Sargur N. Srihari, a professor of computer science at the State University of New York at Buffalo, said the study was by far the most comprehensive effort to prove one of the premises underlying handwriting analysis: that everyone's handw riting is unique.

For the study, 1,500 people copied a four-paragraph letter by hand on paper with a black ballpoint pen three times. The letter included all the letters and numbers. The subjects were representative of the population of the United Sta tes by sex, race, age, education and country of origin.

The letters were scanned into computers, which measured quantitative features, including letter dimensions and pen pressure. ''We were able to establish with a 98 percent confidence that the writ er can be identified,'' the study concluded. Extrapolating to the entire population of the United States, the study's confidence level dropped to 95 percent.

''It's not exactly the sort of 99.9 percent result you would get in DNA testing,'' Professor Srihari said in an interview. Still, he said, ''we got a surprising level of discrimination.''

Professor Mnookin called the study a significant step. ''The claim that everyone's writing is different has always been taken on faith,'' she said. ''The co mputer part of it is kind of sexy, and the courts will probably be thrilled with it.''

The study cautioned that a significant handwriting sample was needed for such confidence. It did not consider forgery or other purposeful efforts to disguise handwr iting.

The study asserted that the accuracy of the computer's analysis would provide a threshold beyond which human analysts could increase accuracy to almost 100 percent by ''measuring the finer features by hand.''

But Michael J. Saks, a law prof essor at Arizona State University, had doubts. ''In most areas of decision making, human beings turn out to be not as good as computers,'' he said.

He suggested that the next step should be testing human analysts with the same set of data.

The stu dy was largely financed by the National Institute of Justice, the research and development agency of the Justice Department. Professor Srihari estimated that it cost $400,000. He said that he had no background in law enforcement-related research and that the government did not try to influence his study.

Critics of handwriting analysis testimony say that law enforcement officials dominate the field and are professionally invested in establishing its reliability.

Handwriting analysts ''wouldn't exi st unless police departments created them,'' Professor Denbeaux said.

Farrell C. Shiver, a forensic document examiner in Woodstock, Ga., said, ''Handwriting analysis has been accepted in the courts for many, many years.''

Even now, ''outside the f ederal arena, there is usually not too much trouble in getting admitted as experts,'' he said. But in federal court, ''the Daubert decision kind of changed the playing field.''

Even before Daubert, ''handwriting evidence never had a sterling reputatio n in court,'' Professor Mnookin said. Its initial acceptance by 19th-century judges was halting and skeptical.

That changed with the trial of Bruno Hauptmann in the Lindbergh baby kidnapping case in 1935. Hauptmann was convicted in part on the basis o f expert testimony that he had written the ransom notes.

''It was the Lindbergh case that put it right up there with fingerprints,'' said D. Michael Risinger, who teaches law at Seton Hall and has studied handwriting evidence extensively.

Professo r Risinger emphasized the limits of Professor Srihari's study, which uses a finite number of relatively long and identical texts in which the writers did not try to disguise their writing.

Identifying the forger of a check, he said, presents a differe nt issue. ''Even in laboratory settings, there is no evidence they can do it,'' he said. Professor Risinger said that at bottom, the study offered substantial proof of a relatively unimportant point. ''I don't think anyone ever claimed there was no signal in that static,'' he said. ''If the signal is there, how good are humans at discerning it? That's the big issue.''

The ultimate question about handwriting analysis, Professor Mnookin said, is one not yet answered by the Supreme Court. ''How reliable

is it supposed to be?'' she asked. ''It's not like DNA profiling, but it's not like psychics either. It's got some purchase, but it's a limited purchase.''